Prince Charming (Owen Moore) flirts with Pickford's "Cinderella" (1914), a film based on the popular fairy tale.

35mm reference print (AFI/Netherlands Filmmuseum Collection, 1994) [1]

Library of Congress Project Report

The Library of Congress (LC) is the primary repository for Mary Pickford films among FIAF archives. The majority of the institution's Pickford material is from the star's personal collection (originally donated in 1946), which contained camera negatives and early generation release prints from her screen career. The institution received additional items in other collections and through copyright deposits. All combined, LC has one hundred and fifty-four of the estimated two hundred five titles Pickford was creatively involved in between 1909-1933. They also have trailers, newsreels, home movies and promotional footage in which she appears. My project was to inspect, compare and catalog this material, which added up to over one million feet of film. I estimated that I would need about a year to do the work and spent an additional 12 months organizing and evaluating the data.

Prince Charming (Owen Moore)

flirts with Pickford's "Cinderella" (1914), a film based on the

popular fairy tale.

35mm reference print (AFI/Netherlands Filmmuseum Collection,

1994) [1]

During the exploratory phase, I was able to correct errors in

Pickford's filmography made by biographers, film historians and scholars. For

instance, the actress has been mistakenly credited in several pictures in which

she does not appear, including "Examination Day at School" (1910),

"At the Duke's Command" (1911), and "From the Bottom of the Sea"

(1911). [2] I verified her appearance

in two titles, "Through the Breakers" (1909), and "A Timely Repentance"

(1912), both of which are rarely linked to the actress. [3]

Mary Pickford (center background)

as an extra in "Through the Breakers" (1909).

35mm reference print (AFI/Tayler Collection, 1976)

[4]

PICKFORD TITLES IN THE PAPER

PRINT COLLECTION

In the summer of 2000, I received funding from the National Endowment for

the Humanities to complete an investigation of Pickford film material at the

LC. Using my newly compiled inventory, I began with an inspection titles from

the Paper Print Collection. Pickford is connected to 108 Biograph Company

titles (1909-1912). As a performer or author. Ninety-three of these are in

the collection of paper film rolls deposited at the LC for copyright purposes.

Often, the only examples of our earliest cinema can be found in paper prints. A handful of Pickford titles fall into this category, including the only extant material of "A Romance of the Western Hills" (1910), and the best surviving 35mm "The Violin Maker of Cremona" (1909), in which she played her first starring film role. The paper prints are also important because they often have the only record of a film's intertitles. Without the paper print intertitles, several Biographs, including "A Midnight Adventure" (1909), "Sorrows of the Unfaithful" (1910), and "The Inner Circle" (1912) cannot be restored. The Paper Print Collection is extremely valuable to U.S. cinema history and nearly all of it has been copied on 35mm and/or 16mm acetate film stock for preservation or research purposes. A few paper print titles have never been preserved, among them are Pickford's appearances in "Muggsy Becomes a Hero" (1910), "Love Among the Roses" (1910), "In the Season of Buds" (1910), and "Just Like a Woman" (1912).

One of five intertitles found

in the original paper print of "A Midnight Adventure" (1909).

16mm reference print (Paper Print Collection, 1969) [5]

Eleanor (Pickford) holds

a gun on Frank (Billy Quirk).

16mm reference print (Paper Print Collection, 1969) [6]

Reference prints (mostly 16mm) exist for the majority of the titles in Paper Print Collection, but a large number of those starring Pickford are not available for study. This situation was created by a series of intricate events. In the 1950's Kemp Niver's lab, Renovare, began transferring the paper prints onto film stock. Most of the Biograph paper titles starring Mary Pickford were not copied. The archive wanted to save funds and avoid redundancy, so titles found in both the Pickford and Paper Print Collections were copied only from the star's film material. Pickford owned approximately 75 original Biograph camera negatives that Niver/Renovare copied (instead of the paper prints) between 1959 and 1963.[7] These films are often out of continuity, need the original intertitles or have reissue titles created in the 1920's. Thankfully, most of the paper prints contain what the Biograph camera negatives lack. In 1974, Niver offered to make 16mm archival negatives of the missed Pickford paper prints and completed the work two years later.[8] Unfortunately, the LC never had positive prints made, so researchers cannot view what are often the most complete and coherent copies.

To complicate matters, the 16mm Biographs from the Pickford Collection have been identified as coming from the Paper Print Collection in LC cataloging records. This mistake of provenance was continued by Niver, who published a reference book making the same claims. The differences in the source materials are easy to discern by simple visual comparison, and can be verified in LC paper files. I have corrected the numerous errors through physical and visual inspection, and from piecing together information from old correspondence, memos, and previous inventories.

FAILED EFFORTS: RESTORING THE BIOGRAPH CAMERA NEGATIVES

The compilation and cataloging of information on the Pickford Biographs was

the most complicated part of my LC research. I not only dealt with issues of

provenance with the Pickford and Paper Print Collections, but with an abandoned

project to restore the camera negatives in the early 1970's. The first transfer

of Biograph camera negatives onto 16mm positive stock was finished in 1963 and

the originals were sent back to Pickford. Unfortunately, the Congress liquidated

the Library's first Motion Picture Division in 1947, and because LC did not

want to store dangerous nitrate, it offered to retain only Pickford's negative

material. The 35mm positive material was to be destroyed.[9]

In a primary example of Pickford's concern for her collection, she requested

that the films be returned to her.[10] The majority of

the holdings were sent back to California in 1959, and Niver returned (by 1963)

the Biograph camera negatives after he completed making LC's 16mm acetate copies.

Two frames (one sprocket

hole each) from the Biograph camera negative for "An Arcadian Maid"

(1910).

35mm Biograph camera negative (Pickford Collection, 1995)

[11]

During this period, the actress planned to donate all of her film, photographic, and promotional items to the Hollywood Museum.[12] Sadly, the proposed institution never materialized and Pickford, now in her seventies, hired Matty Kemp, a former actor and producer, to care for her collection. In 1968, Kemp approached the newly formed American Film Institute (AFI) about preserving Pickford titles on 35mm.[13] Much of Pickford's feature collection had been copied with materials and services donated to the Hollywood Museum by Kodak and Consolidated Film Lab.[14] Henri Langois also funded preservation when the Cinematheque Francaise paid for copies of 20 Pickford film titles to be copied for the French archives collection.[15] Matty Kemp wanted the AFI to cover the cost of restoring the Biograph camera negatives on 35mm safety stock. An agreement was made and 50 original negatives were shipped to the AFI in Washington, DC. The film institute does not have an archive, but financially supports the acquisition and preservation of moving images. The Pickford Biograph camera negatives and the restoration material were to be donated to the LC's Motion Picture Section, which had been recently resurrected in the institution's Prints and Photographs Division.[16]

The AFI had Don Malkames' film laboratory make preservation fine grain masters. The choice of lab was natural, as Biograph had processed negatives with the one perforation sprocket holes, and the Malkames lab possessed the original Biograph printer. Then, in the summer of 1970, the AFI hired UCLA graduate student and Pickford scholar Robert Cushman to assemble the fine grain master material for restoration purposes. Cushman, now curator of Special Collections at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, inspected paper print rolls and early generation prints (from Pickford's Collection), to reconstruct the narrative sequence and placement of original Biograph intertitles. His final report on the project notes the need for newly printed intertitles to be spliced into the fine grains and/or the duplicating negative where he had marked them with yellow film leader.[17] 35mm duplicating negatives and reference prints were to be paid for by the LC. Mary Pickford also expected to receive copies.

THE END RESULT?

It is difficult to deduce what happened to the project after Robert Cushman

finished his work. One reel of Biograph intertitles was compiled from frames

cut out of Pickford's early generation nitrate prints, and an acetate dupe negative

was made. There are also 200 feet of acetate fine grain intertitles. Today,

the Biograph fine grains are as Robert Cushman left them in 1970. The intertitles

were never spliced in, but Cushman's handwritten notes still appear on film

leader, marking where they should be inserted. David Shepard, former AFI acquisition

manager, remembers dupe negatives being made from the fine grain masters, but

there is no evidence to support his claim. Master material for films like "Ramona"

(1910), "A Lucky Toothache" (1910), and "An Indian Summer"

(1912) have intertitles, but only because they are in the original negatives.

From the physical appearances of the film elements and surviving paperwork,

the restoration project seems to have been abandoned and forgotten. During the

1980s, LC made dupe negatives and reference prints from a handful of the assembled

Biograph fine grains. Titles like "The Lonely Villa" (1909)

and "The Informer" (1912) were copied, but no attempts were

made to restore title cards or intertitles.

HISTORY REPEATS ITSELF

In 1995, the Mary Pickford Foundation donated it's 18 remaining Biograph

camera negatives to the LC. The government archive agreed to let Museum of Modern

Art (MoMA) make 35mm preservation fine grain masters (using the Biograph printer)

and 35mm dupe negatives from the newly acquired original nitrate (except "An

Arcadian Maid," 1910). MoMA returned the camera negatives and gave the

LC 35mm reference prints.

A scene from "Simple

Charity" (1910), one of the Biograph titles preserved at MoMA.

35mm reference print (Pickford Collection, 2000)

[18]

I believe the LC agreed to let MoMA copy this Pickford Collection material because the titles complement the New York archive's sizable Biograph collection. MoMA is considered the "Biograph archive" because they house all of the extant Biograph camera negatives, except those found in the Pickford Collection. And the archive has D.W. Griffith's personal film collection. MoMA also agreed to fund the project.

Today, the preservation copies of these Pickford Collection Biographs are

held by MoMA. And though the museum plans to restore them, along with all

of it's other Biograph materials, the enormity of project with an estimated

1,200 reels of camera negatives alone almost guarantees the Pickford's titles

will not be worked on for many years. And without help with proper sequencing

(titles including "A Gold Necklace" (1910) and "So Near,

Yet So Far" (1912) are out of narrative order) and research on

original intertitles, from material already stored at the LC, the restoration

process cannot be completed. Like the Biograph negatives copied by the AFI,

these Pickford titles remain in seemingly unnecessary a state of limbo.

Mary Pickford as Priscilla

in "An Arcadian Maid" (1910).

Positive image from 35mm Biograph camera negative (Pickford

Collection, 1995) [19]

The LC's decision to let another archive preserve/restore any part of the Pickford Collection was both illogical and impractical. To prevent unnecessary complications and ensure that the Pickford Biographs are restored and accessible, I believe the restoration of these materials should be handled by the LC. Though, I agree that institutions must work together to help fund preservation projects, and do not quarrel with another FIAF archive's desire to complete a collection that has both historical and institutional importance. I do question the decision to allow another archive to preserve and restore materials from an LC collection. Mary Pickford had possession of these films since the mid-1920s, and she wanted in life and willed on her death that they be cared for by the LC. The Biograph camera negatives not only represent an important part of her career, but also her business savvy in making the acquisition. Pickford's intentions were to see these particular titles preserved, not simply housed, by the LC.

ADDITIONAL BIOGRAPH PRESERVATION PRIORITIES AND RARE MATERIALS

The Motion Picture Section at LC also holds a number of early generation prints

of Pickford Biographs in need of preservation. Complete versions of "The

Indian Runner's Romance" (1909), "The Call to Arms" (1910),

as well as a tinted print of "My Baby" (1912) are just three of

the nitrate positives that need preservation. Other titles may not be the

best of the extant nitrate, but are often the most accurate evidence of a

film's original content. For instance, they indicate correct intertitles,

scene placement, and missing footage. They are therefore essential for reference

purposes when restoring better material to the original release version. In

fact, without them accurate restoration may be impossible.

I have earmarked rare material preserved from nitrate for future work. Two 1912 titles, "A Lodging for the Night" and "The School Teacher and the Waif" were copied from camera negative material onto 16mm positive stock by Kemp Niver in 1959 and 1960. No other prints or negatives were made and the original elements do not survive. The 16mm reference prints, now upgraded to masters, are all that remain of the camera negatives. Two nitrate positives (now lost to decomposition) for "Fate's Interception" and "The Old Actor" (both 1912), were copied at the USDA Lab in 1956 and have turned out to be the best extant material. Both titles survive on 35mm dupe negatives originally copied from early generation nitrate prints. The camera negative for "The Old Actor" does not survive and it appears to have never been copied. The British Film Institute has the only other material known to exist on this title, but its estimated footage is short and probably not from an original print. "Fate's Interception" has a camera negative stored at the LC and preserved by MoMA, but the material is out of narrative sequence and lacks intertitles. Without restoration, the LC's 35mm acetate negative on "Fate's Interception" remains the best version to survive.

RECENT ACQUISITIONS

There is always a chance that the LC will acquire new or better material on

the Pickford Biograph titles. The 1994 AFI donation of a nitrate positive

of The Indian Runner's Romance (1909) in Australia and a 2000 UCLA

Film and Television Archive (UCLA) gift of nitrate footage from "The

Informer" (1912) are good examples. In 1970, when Robert Cushman was

restoring the fine grain master for "The Indian Runner's Romance"

he could find no version with intertitles. Research convinced him that the

film was released with intertitles, so new ones were created. Recreating "lost"

intertitles is the only misstep in Cushman's work, which to date has been

by far the best effort to restore Mary Pickford's Biograph titles.

In 1972, the AFI acquired a nitrate print of "The Indian Runner's Romance"

with intertitles from the Tayler Collection. Due to decomposition, only three

intertitles were found, but in 1994 the National Film and Sound Archive in

Australia turned up a print. The nitrate (donated to the LC by the AFI) suffers

from mild to severe decomposition, but has all five original intertitles.

Therefore, correct placement of these titles can be determined and the film

can be restored. And in February of 2000, Jere Guldin, Film Preservationist

at UCLA, contacted the LC about some decomposing material donated to the archive

from "The Informer." Guldin believed that footage from the film's

beginning (which was in fair condition) could be useful for the LC's future

restoration. To date the LC had only began the process by combining material

from two nitrate prints in the AFI/Pickford Collection. After reviewing all

of the archive's film elements of "The Informer" and comparing it

with the cutting continuity on file with the US Copyright office, I was able

to determine that the best version was the LC's camera negative. Though scenes

are out of order and the intertitles are missing, all the shots are accounted

for. Nevertheless, Jere Guldin's discovery is important because the material

contains the opening intertitle found in the cutting continuity, but not in

any surviving version. His find guaranteed that this intertitle was in the

release version, and now the LC can finish restoration on an important Biograph.

The opening intertitle from

"The Informer" (1912), previously missing from all extant material,

but later found on a nitrate print acquired by UCLA in 1999.

35mm reference print (UCLA Film and Television Archive Collection,

2000) [20]

The large number of elements and complicated history of Pickford Biograph materials make preservation and restoration of these films complex. I have offered the LC a list of titles and elements recommended for immediate and future lab work. To handle the difficult task I suggest the archive begin with unique and unpreserved film materials, then focus on the best negatives, prints, and paper to survive in FIAF archives. Once these titles have been completed, I believe the LC should preserve at least one copy of the remaining Pickford Biograph titles from her personal collection. All but one are single reel titles. This makes the project both financially feasible and less time-consuming than feature preservation/restoration work. No argument seems necessary to prove the historical importance of saving productions starring one the greatest icons of film's pioneer era.

TREASURES FROM THE INDEPENDENT MOTION PICTURE COMPANY

At the end of 1910, Mary Pickford left the Biograph Company to pursue both

acting and writing at the Independent Motion Picture Company (IMP). The enterprise

was then a renegade film company under the direction of Thomas Ince, shooting

movies in Cuba to avoid the tyranny of the Motion Picture Patents Company.

A number of Pickford productions were filmed in Cuba, including "Artful

Kate"and "In Old Madrid (both 1911)." All in all, Pickford

appeared in an estimated thirty-three short films during her ten-month stay.

But unlike Biograph productions, few IMP titles are known to survive, making

preservation of all extant materials a top priority. Only 11 Pickford IMPs

have been located in FIAF archives. In addition, only two of LC's eight Pickford

Imps have been adequately preserved. The remainder are urgently recommended

for copying.

Sisters Mary and Lottie Pickford

play lovers in the IMP title "Sweet Memories" (1911), the only

extant film starring the entire Pickford family.

35mm reference print (AFI/Vick-Roy Collection, 1975)

[21]

Four of the eight IMP titles held at the LC, "The Dream," "The

Lighthouse Keeper," "In the Sultan's Garden," and "Sweet

Memories" (all 1911) are unique to the government collection.

Of the four, "The Dream," a title Pickford wrote, is the only one

with adequate preservation. A tinted nitrate positive of "The Lighthouse

Keeper" was acquired in the AFI: Nichol Collection in 1969. It

is the only extant copy of the title in any FIAF archive. In 1977, a 35mm

acetate dupe negative and reference print were made in black and white. The

quality of the preservation is poor, but it may be possible to get better

material on this title before it is too late. The unique nitrate material

is decomposing at a rapid rate, so lab work will have to be scheduled in the

near future. Restoration of the tints is possible, so I created a color log

for every nitrate print with the additive process.

Pickford and Owen Moore in

"The Dream" (1911) a story she wrote for the Independent Motion Picture

Company.

35mm reference print (AFI/Vick-Roy Collection, 1986)

[22]

Unfortunately, the condition of this element is such that inferior

safety material made twenty-five years ago may be all that history has left

us. Unlike "The Lighthouse Keeper," there are two different extant

copies of "In the Sultan's Garden." The LC has both: a 35mm acetate

dupe negative and reference print made from Pickford's nitrate print in 1956

and a 35mm tinted nitrate print in the AFI/Post Collection. The nitrate is

in fair condition, but it is over a one hundred feet shorter than Pickford's

copy. Only a shot by shot comparison will determine if better material can

be obtained. The 35mm safety copy has continuity problems and jumps in action,

which makes more detailed study of the nitrate version a necessity.

Mary Pickford plays a harem

girl in "In the Sultan's Garden" (1911).

35mm tinted nitrate positive (AFI/Post Collection, 1971)

[23]

Fragments of unrelated footage are often found spliced into reels of film. A collector or exhibitor may add material from another source for narrative purposes, or simply use it at the head or tail for leader. During my research, I noticed a few feet of tacked-on footage at the head of the nitrate print of "In the Sultan's Garden." Due to serious continuity problems in Pickford's safety copies, I wanted to take a closer look at the nitrate in the AFI/Post Collection, and hoped that this print offered better narrative order and possibly missing footage which could be used for future restoration. Knowing that further comparative research would have to be done, I asked LC staff to separate the unrelated footage at the head from the rest of the reel.

Usually small scraps of nitrate are unimportant and archives often dispose of them. But George Willeman, the LC's Nitrate Film Vault Work Leader, noticed that the fragment I had removed was Kinemacolor, an early color film process. He saved it for further evaluation and later identified it as footage of "former US President William Howard Taft shown on an upper deck of a steamship." The LC believes this is the only color moving image footage of Taft to survive. The support of archival staff during my project and in this case their professional curiosity led to an important discovery out of the realm of my search for Mary Pickford's film legacy.

A Kinemacolor fragment of

President William H. Taft on the deck of a steamship ca. 1914 that was used

as leader at the head of a nitrate print of the Pickford short "In the

Sultan's Garden"

35mm nitrate positive (AFI/Post, 1971)

[24]

PRESERVING MULTIPLE VERSIONS

Additional footage was also found on "Sweet Memories," a nitrate

one-reeler, but unlike the unrelated material attached to "In the Sultan's

Garden," it was supposed to be there. The LC has two unique nitrate prints

of the Pickford film. One version, in the AFI/Vick-Roy Collection, is 100

feet shorter than the copy in the AFI/McPherson Collection. Oddly enough,

while attempting to document what was missing from the abbreviated print,

I discovered an additional scene not in the extended copy. I quickly realized

both prints were altered from its original release version. The AFI/Vick-Roy

print has every scene found in the longer AFI/McPherson copy, but slightly

shortened. The film was most likely edited to improve its pace, which is often

weighed down by overly long shots. On the other hand the AFI/McPherson copy

is missing a scene found in the condensed AFI/Vick-Roy print, possibly cut

to enhance the flow of the original edit. Finally, "Sweet Memories,"

based on a poem, has a simple editing pattern. Each scene is followed by a

verse (intertitle), except near the end when two consecutive shots are placed

before an intertitle. I believe the late change in the editing pattern is

distracting, and that the scene was excised because the shot it is not vital

to the story. The two different versions of "Sweet Memories" not

only illustrates the technical skill and creativity involved in constructing

a film narrative, but raise a number of academic issues regarding cinema restoration.

Old movies are often reedited for one purpose or another over time. Production and/or distribution companies may alter a film from its original version for reissue, or an exhibitor might trim frames to shorten the picture's length. Moving images are now edited for television and cannibalized for use as stock footage. State censors, collectors, archivists, even projectors can be responsible for modifying or eliminating footage in a film. Whether intentional or accidental, changes to a "finished" production can profoundly effect how we understand that work. For moving image archivists and preservation specialists, the methodological and ethical dilemmas in restoring cinematic works for posterity are often daunting. The challenge of defining and reconstructing a "definitive" version of a film is demonstrated by the discovery of two distinct copies of Mary Pickford's "Sweet Memories."

The additional footage found in the abbreviated version of "Sweet Memories" is not just important to persons with a technical or academic interest in film. The extra material cut from the AFI/McPherson print also has biographical significance to the life and career of Mary Pickford. The discovered scene is of Charlotte and Jack Pickford, Mary's mother and brother, who also starred in the film. The two are in a graveyard grieving over the loss of the husband/father. The 16 feet of footage not only represents the power of Mary Pickford's early fame (IMP was willing to employ the entire family to get Mary), but it eerily reflects an actual incident in the life of the Pickford clan, the early death of Mary's father John. Extra material, like the scenes found in "Sweet Memories" or "In the Sultan's Garden" illustrate the necessity of detailed moving image research and the potential relevance/significance of even a fragment of film footage.

The graveyard scene from

"Sweet Memories" (1911) with Jack and Charlotte Pickford.

35mm reference print (AFI/Vick Roy Collection, 1975) [25]

IMP PRESERVATION PRIORITIES AND UNIQUE FOOTAGE

Film material on the remaining four Pickford IMP titles, "Artful Kate,"

"In Old Madrid," "'Tween Two Loves," and "When the

Cat's Away" (all 1911) exist at other FIAF archives, but the prints

held by the LC are the best in quality and completeness. "When the Cat's

Away," a 1998 acquisition in the AFI/Parker Collection, was promptly

preserved and a 35mm reference print is available. The film was originally

released on a split-reel with "The Mirror" (1911), a lost title

that I (re)discovered at the George Eastman House in 1997. Not only are the

films valuable in themselves, it is unique that two halves of a split-reel

survive (at different institutions) and were discovered separately in the

last five years.

Pickford plays a young mother

who rescues her child from a fire in "'Tween Two Loves" (1911).

35mm tinted nitrate positive (AFI/Cohen Collection, 1978)

[26]

The other three IMP titles have not fared as well. "Artful Kate" and "In Old Madrid" survive in nitrate elements that have never been copied, and a tinted print of "'Tween Two Loves" was inadequately preserved (in black and white) in 1978. I also found fragments of two additional Imps, "At a Quarter of Two" (1911) and "A Timely Repentance" (1912), at the LC. I discovered one fragment when I viewed a clip of an unidentified film starring Mary Pickford and her real-life husband Owen Moore at the end of a promotional Hollywood series called "Screen Snapshots" (1920).The footage was too early to be from a feature film, and because I know Pickford's work so well, it was easy to eliminate Biograph and Majestic (where she and Moore later worked) as possible production companies. After researching the plot synopses of all of the IMP titles, I identified the material as being from a lost film called "At a Quarter of Two." Pickford plays the mother of a sick child whose life is put at risk by a burglar.

A fragment from a lost IMP

title "A Quarter of Two" (1911) found in an episode of Screen Snapshots

(1920).

16mm reference print (AFI/Ableson Collection, 1995)

[27]

"A Timely Repentance" was the last Pickford film released by IMP in 1912. The actress had left the production company in late 1911 to work at Majestic, then returned to Biograph at the beginning of the new year. The split between Pickford and IMP was tumultuous, with a lawsuit tried in a New York City courtroom that eventually ruled in Pickford's favor. But though she won the war, IMP had one more volley to throw her way. Pickford's Biograph productions were already being shown in theaters when IMP decided to release "A Timely Repentance." It is the story of a wife who abandons her family to run off with another man, then changes her mind after viewing a similar tale in a movie with a tragic end. Pickford plays the errant wife in the film within a film, entitled "A Wife's Desertion." A scene, most likely from "The Dream," shows the wife running off with a wealthy man while the distraught husband commits suicide.

The insertion of the Pickford material into "A Timely Repentance" may have been purely a business decision. IMP knew the actress was a box office draw and cannibalizing an old film saved money that would have been spent to create the film within a film. Moving Picture World, a film magazine friendly to independent movie companies, did promote Pickford's appearance in "A Timely Repentance" building an audience on her name. After an ugly legal battle it is likely that this was a professional jab at the actress who had abandoned both IMP and Majestic just months before, and was having marital problems with her husband, "The Dream" costar Owen Moore.

Little information can be gathered from the tiny eight-scene paper fragment that exists from "A Timely Repentance," so the above theory is based on information culled from film reviews, an 1911 newspaper story from the "New York Times," and Eileen Whitfield's 1997 Pickford biography. Sadly, Mary Pickford does not appear in the surviving fragment (submitted for copyright in 1912) making it impossible to get a sense of how the footage of her was used. But finding any footage from Pickford's IMP films is especially important because so much of her work from this period is lost. Every inch of material is vital to a greater understanding of the star's post-Biograph career.

RESCUING THE PICKFORD FEATURE FILMS

Mary Pickford went back to work at Biograph in early 1912, but left a year

later to make features at the Famous Players film company. The actress appeared

in 52 full-length films between 1913 and 1933. The LC has 32 of these titles

in its motion picture archive, the majority donated in the Pickford Collection.

The star's original gift (received in 1946) included camera negatives (American

and foreign), work prints, and early generation or re-release prints. LC had

agreed to preserve all Pickford film materials and began the process almost

immediately. But progress took a sharp turn for the worse when the US Congress

liquidated the film department in the summer of 1947 after only a few of the

actress's films were copied. Pickford's collection went into a kind of limbo

until James Card, curator of the film department at the George Eastman House,

took an interest.

Pickford and Card met at the Museum's opening in fall of 1949, and a year later

negotiations began between GEH and LC to preserve materials from her collection.

Between 1951-1952, a handful of Pickford titles --"The Little American"

(1917), "Little Annie Rooney" (1925), "A Little Princess"

(1917), and "Through the Back Door" (1921) were preserved from the

actress's nitrate collection by GEH. With funds from the Ford Foundation and

Eastman Kodak, Card had 35mm fine grain masters or dupe negatives made, and

16mm prints were given to the LC. Later, in 1956, Card convinced Pickford to

donate $10,000 towards the preservation of her remaining collection, and LC

received funds to generate one print of every title for both archives. In an

effort to preserve as much nitrate as possible with the money, LC decided to

only have 16mm prints created from the 35mm negatives. Or, when only positive

materials were available, they made a 35mm acetate dupe negative, then a 16mm

print. Pickford, a powerful producer and Hollywood figure, owned or purchased

the American and/or foreign camera negatives for over half her film output.

Sadly, this meant the majority of her collection was copied only on 16mm stock.

The LC was aware they were not making preservation material, but the institution

was not in a financial position to do better. It must be stressed that there

was not even a Motion Picture Department in 1956. The fear of losing the collection

to decomposition, fire, or theft made the 16mm prints better than nothing at

all.

Pickford with director Cecil

B. Demille on the set of "The Little American."

The U.S.D.A. film lab began transferring the Pickford Collection from nitrate to acetate stock in 1956. And despite mistakes which seem obvious in hindsight, the project (completed a year later) was responsible for saving a few feature titles from extinction. "The Foundling" (1916), "Johanna Enlists" (1918), "Less than the Dust" (1916), and "Poor Little Peppina" (1916) exist today only due to the 1956 collaboration of the LC, GEH, and Mary Pickford. Unfortunately, the only 35mm dupe negative copied was for "Less than the Dust." The film is lacking its final reel, but is extremely important because it was the first feature Pickford produced on her own.

The LC is unable to locate the 16mm archival positives of "Johanna Enlists" and "Poor Little Peppina," so the best of the surviving material now resides at GEH, which also received prints in 1957. LC had 16mm dupe negatives and prints made from the 16mm archival positive in the early 1970's, and fair/poor quality screening copies are available for research. Unfortunately, LC is also missing the 16mm dupe negative of "Poor Little Peppina," copied in 1971, leaving the archive with extremely poor quality material on this title. The LC is working on a 35mm blowup of "The Foundling," and plans to restore the continuity lacking in several scenes. Blowups of 16mm material will be necessary to restore a number of the Pickford features.

"ESMERALDA"

It is important not to lose sight of what was (and can still be) gained from

Pickford materials. Valuable lessons can be learned from past mistakes. The

LC lost its best chance to preserve the Pickford Collection features in 1956

when the institution decided to make 16mm copies of most of the nitrate in her

possession. But a worse error in judgment was to do nothing at all. One of the

biggest losses from the Pickford Collection is her 1915 version of "Esmeralda."

The star had three positive reels out of five when she donated her collection

in 1946. After the liquidation of the LC's film department in 1947, the reels

were shelved, as were all moving images collections held at this time. By 1956,

two more reels had decomposed, and the last surviving reel was never copied

because film was deemed "incomplete". Obviously, the film was lacking

most of its parts, but Pickford's copy of "Esmeralda" was the only

one ever found. The title is now considered lost, which highlights the significance

of preserving unique materials even when the film is not complete.

Ad for the

lost Pickford feature "Esmeralda."

WHAT'S IN A NAME? THE MISIDENTIFICATION OF "FOREVER YOURS"

The perplexing and unfortunate history of "Forever Yours" (1930) at

the LC signals another significant loss to the collection. In 1946, when the

actress deposited her movie holdings, several nitrate reels of a film entitled

"Forever Yours" were included. The material was identified as the

American release version of a 1936 British film "Forget Me Not." The

film, made by Alexander Korda's London Film Productions, was released in the

United States as "Forever Yours" by Grand National Films in 1937.

Its doubtful, though not impossible, that Pickford had material from Korda's

feature. Much more likely, the footage was from an abandoned 1930 Pickford production,

also called "Forever Yours" directed by Marshall Neilan. The film

was later reshot with director Frank Borzage and released in 1933 as "Secrets."

The probable error in identification may have occurred due to Pickford's position at United Artists (UA), a distribution company she co-founded in 1919. After Art Cinema, one of the company's distributing units, was dissolved in 1936, the actress acquired numerous UA titles, including D.W. Griffith's "Drums of Love" (1928) and King Vidor's "Street Scene" (1931). In 1935, Alexander Korda became a partner in UA and began distributing his productions through the company. But he did not release "Forever Yours" through UA. Korda's involvement in UA, Pickford's acquisition of UA films, and ignorance about her own 1930 production may all have been causes of the misidentification.

Pickford was not a collector of cinema to which she was not professionally or personally connected, making the acquisition of Korda's material even more doubtful. Her collection covered mostly features, short, promotional material, newsreels, and home movies from the actress's motion picture career. She owned a few Biograph productions in which she did not appear, including "Examination Day at School" (1910), "His New Lid" (1910), and "The House of Discord" (1913). Pickford also had features starring her siblings Jack and Lottie, and film properties from UA.

The misidentification of "Forever Yours" as a Korda picture is even more probable due to the discovery of footage from the Pickford/Neilan production. In 1996, two hundred and ninety-four feet of "Forever Yours" (1930) was discovered at the LC in a mislabeled can. The small reel of nitrate picture positive had been sent to LC in 1989 by Pickford Company manager Matty Kemp, who believed it to be an "extra" reel of the already donated Pickford feature "Kiki" (1931). Seven years later LC staff properly identified the footage as stock shots from the unfinished 1930 production of "Forever Yours." The archive promptly preserved it, but unfortunately much more would survive today if the LC's motion picture department had not been liquidated.

Mary Pickford and Kenneth

MacKenna in a scene from the never released production of "Forever Yours."

35mm reference print (Pickford Collection, 1996)

[28]

Pickford's "Forever Yours," donated to the LC in 1946, was slated for lab work in the summer of 1947. Like "Esmeralda," the material was shelved when LC's film department was dismantled. In 1956, during the Pickford-funded project to copy her nitrate onto safety stock, the six reels of picture and track negative, six reels of picture positive, nine reels of negative and two reels of positive stock shots were deemed "not suitable for copying." Some of this material was likely destroyed due to decomposition, but several reels were definitely returned to Pickford, showing up in inventories of the star's holdings as late as 1975. Fifty years after the LC received her collection, the institution finally salvaged something from "Forever Yours."

WHERE TO GO FROM HERE

The fate of "Esmeralda" and "Forever Yours" is extremely

regrettable. Sadly, the story of these titles is not unique. Motion picture

archives lose material every day because of a lack of funds, and few archives

can afford a staff that can do extensive research on one particular collection.

Without a comprehensive study of extant materials archives will continue to

make preventable mistakes that cost us our film heritage. Still, though the

LC has missed many opportunities to save the feature film legacy of Mary Pickford,

there are a number of features that can still be adequately preserved before

it is too late. The restoration of "Sparrows" (1926) and "Kiki"

(1931) are top priorities.

A lavender tinted frame from

a nitrate print of "Sparrows" (1926).

35mm tinted nitrate positive (Pickford Collection, 1995)

[29]

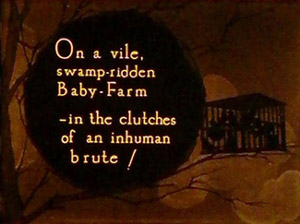

"Sparrows," directed by William Beaudine, is one of the actress's two final silent films and is also thought to be one of her best. The tale of orphaned children attempting to survive on a "baby farm" has all the elements of a great Pickford movie. The suspenseful drama cleverly uses a mix of tragedy and comedy to tell the story of a teenage heroine who saves herself and others from an abusive guardian, murderous kidnappers, and a swamp full of alligators. Pickford often starred in dark tales, but the almost gothic visual style of this production is unique in her career. The exterior set was truly creepy with long leafless branches, hanging moss, and a treacherous swamp. The interior sets were equally depressing. The children live in a desolate barn without adequate heat, food, or bedding, and their cruel guardian, Mr. Grimes, lives in a dirty, broken-down shack with his family.

Amazingly, a tinted print of "Sparrows" was received (in excellent condition) from the Mary Pickford Library (MPL) with several boxes of nitrate materials in 1995. Though it is missing three reels, the remaining six are among the jewels of Pickford's collection. By collaborating with other FIAF archives and the MPL, the missing material can be located and the film restored. The only other FIAF archive known to have 35mm material on "Sparrows" is the Cinematheque in Paris, which received a print on sound stock in the mid-1960s. The LC material is without a doubt the best extant and should be preserved as soon as possible.

Pickford's feature "Kiki" (1931), a remake of a 1926 movie starring Norma Talmadge, is a primary candidate for preservation/restoration. The film, one of four talking pictures the actress made before retiring from the screen in 1933, has never been preserved. A 16mm print was made for both LC and GEH in 1956 before the nitrate material was returned to Pickford. Those original film elements were (again) deposited at the LC in compliance with the actress's will in 1981. Though Pickford had requested copies of her entire collection be donated to LC on her death, only five titles were sent prior to 1995. Tragically, by the mid-1990s, almost all of the feature titles were lost or only partially survived due to decomposition. The preventable loss of numerous camera negatives and early generation prints from films made as early as 1914 is distressing. Fortunately, "Kiki" and a few other Pickford titles can still be saved.

ADDITIONAL PICKFORD NITRATE PRESERVATION PRIORITIES

Tinted prints of

two features, "Madame Butterfly" (1915) and "Little Annie Rooney"

(1925) are complete, but only the first two tinted reels survive of a print

from a third film, "Rags" (1915). The tinted prints are the last

of the extant nitrate on these titles, and have all been copied at one time

by LC or an outside party. Still, the previous work is unsatisfactory as far

as preservation is concerned, leaving the best and most important work to

be done.

Pickford as Alice McCloud

in a scene from "Rags."

35mm tinted nitrate positive (Pickford Collection, 1995)

[30]

RESTORING THE PICKFORD FAVORITES

"Rags" and "Tess of the Storm Country" (1922) are

among Pickford's most successful features. In both movies, the actress plays

the kind of role her audiences loved--the impoverished but feisty heroine.

Luckily, Pickford loved to play such roles, creating a gallery of willful

and fiery girls from the lower classes in "Fanchon the Cricket"

(1915), "The Eternal Grind" (1916), and "M'liss" (1918)

to name only a few. Pickford loved the role of Tessibel Skinner (her most

physically and verbally aggressive role) so much that she portrayed her in

two versions (1914 and 1922) of "Tess of the Storm Country." Her

character in "Rags" (1915) is written and performed in the

same vein. Both roles were key in defining Pickford's screen persona. For

this reason alone, these films deserve a full and careful restoration.

Opening title card from "Tess

of the Storm Country" (1922).

16mm reference print (Pickford Collection, 1979)

[31]

"Tess of the Storm Country" (both 1914 and 1922) and "Rags"

were copied at the U.S.D.A film lab prior to the liquidation of the LC's motion

picture department in the summer 1947. They are in decent physical condition

and have good visual quality. Unfortunately, the original size and scope of

the 35mm material is lost because LC chose to copy onto 16mm stock. Without

substantial 35mm footage, the 16mm is the best material left. Copied nearly

a decade before GEH's positive, the LC 16mm is most likely the better of the

two prints made from Pickford's nitrate elements. Of all of the Pickford films

that have not survived on 35mm stock, "Tess of the Storm Country"

(1922) is the most shocking. The 10 reel feature is critical to understanding

the phenomenal success of the actress, making it one of her most important

films.

Mary Pickford as Tessibel

Skinner

16mm reference print (Pickford Collection, 1979)

[32]

In 1965, the Cinematheque in Paris received a 35mm print of "Rags" on sound stock. The film, already suffering from decomposition in 1947, is probably incomplete. Regardless of the condition or completeness of safety material in France, the LC needs to preserve its two 35mm tinted nitrate reels as soon as possible. The government archive's 16mm archival positive was copied a decade before GEH's 16mm print (in 1956) and almost 20 years before the Cinematheque's 35mm. The best of the extant material is at LC. It would be tragic to lose the remaining two reels of nitrate before the preservation/restoration of "Rags" is completed.

"SUDS"

A more vulnerable Pickford character can be found in "Suds" (1920).

The actress loved to play the strong and fiery heroines, but she also had a

fondness for portraying the downtrodden "slavey". A "slavey"

was a young woman who worked as a household servant performing the more undesirable

chores. Pickford played this type of character as shy, awkward, self conscious,

and often unattractive. The polar opposites of her Tess. In "Suds,"

she portrays Amanda Afflick, a laundress who lives and works in a London

slum. The roots of this character can be found in other Pickford films including

"The Foundling" (1916) and "Stella Maris" (1918), but also

Biographs like "Simple Charity" (1910) and "The Unwelcome Guest"

(1913).

Frames from a deteriorating

nitrate print of "Suds."

35mm tinted nitrate positive (Pickford Collection, 1995) [33]

Several reels from the 1920 feature "Suds" were donated to LC in 1995, but only four reels (1-4) of the foreign camera negative and one reel (5) positive from the American version could be salvaged. Institutions have 16mm material on "Suds," including GEH and the British Film Institute. The only other 35mm material in a FIAF archive is at the Cinematheque in Paris. The French archive paid and received an acetate print of the Pickford title (copied on sound stock) from her company in 1965. Little is known about the status and condition of the French material. The Pickford Foundation also has a few acetate 35mm negatives and prints of unknown quality in its private collection. With so much information on the various 35mm materials unknown, I recommended the LC preserve its remaining nitrate reels until further information is gathered. The archive copied the material with mixed results, but a safety copy is now available for the institution's research and/or restoration purposes.

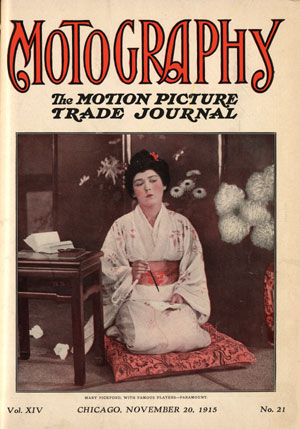

REPRESENTING DIVERSITY

Ethnicity and race, as well as class, were often central to Pickford's character.

The actress clearly saw herself as an "everywoman". She was Scottish

in "The Pride of the Clan" (1917), Irish in "Amarilly of Clothes-Line

Alley" (1918), and Italian in two films, "Poor Little Peppina"

(1916) and "The Love Light" (1921). Pickford was also Belgian, British,

Dutch, and French. In "The Hoodlum" (1919) and "Little Annie

Rooney" (1925) she was one of the diverse residents living in a

New York City tenement. At Biograph, she often played and was well received

in Native American, Mexican, and Spanish roles. Pickford portrayed a number

of women who were not white. The films, "Little Pal" (1915), "Less

than the Dust" (1916), and "Madame Butterfly" (1915),

reveal the racial stereotyping and cultural ignorance of the period. Still,

the positive effect of "America's Sweetheart" portraying an intellectually

curious Indian girl ("Less than the Dust"), the last surviving chieftain

of a village in Scotland ("The Pride of the Clan"), or a sympathetic

and mistreated Japanese woman ("Madame Butterfly") cannot be ignored.

Pickford on the cover of

Motography as Cho-Cho-San from "Madame Butterfly."

The best of the extant materials on "Less than the Dust," "Little Annie Rooney," and "Madame Butterfly" are at the LC leaving the institution as the responsible party in terms of their preservation and/or restoration. A commitment to work these titles into the LC's preservation budgets over the next few years is necessary to save them for posterity.

"Less than the Dust" (1916) was the first film produced by the Pickford Film Corporation. The actress/producer donated a tinted nitrate print thirty years after its original release to the LC. In 1956, a 35mm dupe negative and two 16mm prints (one for GEH) were copied from six of the film's original seven reels before the nitrate was returned to Pickford. The last reel is considered lost. UCLA has a fragment from the first reel of Pickford's (early generation) tinted print, but the best material is LC's 35mm safety negative. During a recent inspection, I noticed that the emulsion on the 35mm is beginning to separate from the base. A fine grain master and a 35mm viewing copy should be made before any further loss occurs.

The MPL donated a tinted nitrate print of "Little Annie Rooney" to LC in 1995. The material has not been preserved by the government archive. LC has a 16mm print in the Pickford Collection, copied with funds provided by GEH in 1952. James Card, GEH motion picture curator, selected reels two through ten from Pickford's camera negative, and likely used the star's nitrate positive (now stored at LC) for reel one. GEH has five reels of 35mm fine grain, one reel of 35mm dupe negative, and a 16mm print. There are several problems with the LC/GEH material, including shots that are out of order, flash frames with tinting instructions, and heavy scratches printed in. The best of the extant material (in good physical condition with proper continuity) is LC's unpreserved 35mm tinted nitrate print. The print has been copied by Killian Classics and the MPL. It may also have the source for a 35mm print (on sound stock) sent to the Cinematheque in Paris in 1965. The LC needs to preserve the nitrate material and, if possible, provide a 35mm viewing copy. I recorded the tints from the original element during my research and the information is available to the LC for restoration purposes.

LC has the best of the extant

material from "Little Annie Rooney."

35mm tinted nitrate negative (Pickford Collection, 1995)

[34]

Mary Pickford had a camera negative of "Madame Butterfly." James Card at GEH borrowed it from LC in 1956 to make a 35mm material. No 35mm material was ever processed into the collections at either archive, but GEH and LC did get 16mm prints. The original was sent back to Pickford, and only a fragment survives today. In 1989 the remaining material was sent to LC and two years later it was preserved. Thankfully an early generation 35mm tinted nitrate print was donated to LC in the AFI/Paramount Collection. The LC preserved the material in 1970 and eight years later a grainy and scratched 35mm b/w print was made, revealing the inadequacies of the preservation. To assist any future restoration, I recorded "Madame Butterfly's" color scheme, as I did for all the tinted material I inspected.

RESTORED FEATURES

During the 1990s, the LC completed restorations on two Pickford features, "Cinderella" (1914), one of the earliest Pickford features to survive, was discovered in Holland and is now at the LC in a tinted nitrate print. It was copied once in the 1970s, but later deemed inadequate by current preservation standards. The film was restored (without translating the Dutch intertitles) in the early 1990s.

Prince Charming dreams about

"Cinderella".

35mm reference print (AFI/Netherlands Filmmuseum Collection,

1994) [35]

The second restoration, "Coquette" (1929), is Pickford's first talking

picture and earned her an Oscar for best actress. The film was released in 1929,

when the film industry was still making the transition from silent to sound

pictures, so a silent and "talking" version were made. In a major

undertaking, the LC (which has nitrate material on each version) restored both

versions between the late 1980s-early 1990s.

"THE PRIDE OF THE CLAN"

Two 16mm prints of "The Pride of the Clan" were copied for the

LC and GEH at the USDA lab in 1956 from seven reels of original negative acquired

from Pickford a decade before. A report documents, like with most of the features,

the "continuity was arranged" and the "titles were matched to

the scenes" before it was printed. Though LC believed the film was complete,

only six reels were found and used to make the 16mm material. The negative was

definitely lacking a reel or more of footage and numerous intertitles. Indeed,

a large number of Pickford features, copied for the LC and GEH in 1956, are

missing key scenes and intertitles. Some footage was cut out for use in an early

(abandoned) Pickford documentary "Cavalcade," but losses of material

could have occurred for a number of reasons. Because of this, and with so many

Pickford films pieced together (in a year long project), the continuity and

completeness of the majority of features from her collection are questionable.

"The Pride of the Clan" is unfortunately one of those titles.

Photograph

of Mary Pickford on the set of "The Pride of the Clan."

(Author's Collection)

During my research, I came across correspondence that led me to additional footage from this film. In late 1969, the Pickford Company manager Matty Kemp loaned AFI archivist David Shepard four 35mm reels of acetate fine grain from company's collection. Kemp claimed the other three nitrate reels had decomposed because Pickford refused to pay for preservation, but it is also likely they were among the number of reels lost in a nitrate fire while Kemp was working with old film at Pickfair in 1965. Shepard discovered that Pickford's four reels contained footage missing in LC's 16mm print, and that between the two copies the title could be restored. According to correspondence, a 16mm print was made using both the Pickford and LC copies for use in a future restoration. Unfortunately, there is no information on the 35mm print that was shown at an AFI screening at the Lincoln Center in 1970. Also, neither the LC or the MPL received any of the material copied by David Shepard for the AFI, and no official restoration project was ever undertaken.

"The Pride of the Clan," a visually stunning film shot on location in Marblehead, Massachusetts by director Maurice Tourneur, is considered one of the best of Pickford's early pictures. Scholar Richard Koszarski, was so impressed with the film's composition, acting and editing, he wrote it was "clearly ten years ahead of its time." After I informed the LC and the MPL about the problems with their materials they agreed to collaborate on a restoration. The joint venture emphasizes the importance of archives, scholars, and owners of private collections working together to save our film heritage.

PICKFORD RARITIES

Some of the more unique Pickford items housed at the LC are newsreels,

film trailers, home movies, and promotional footage. These items were most

often used to promote Pickford, her latest picture, or spread personal news

like the actress's engagement to Charles "Buddy" Rogers found in

the outtakes from two newsreel companies. The newsreel outtakes and a number

of these rare materials are yet to be preserved.

Only three trailers from her career are known to exist. One is a sepia tinted roll promoting "Sparrows," a dupe negative (originally located in Australia) for the silent version of "Coquette" (1929), and an exhibitor's trailer for her last feature film "Secrets." None of these rare items (all on nitrate) have been preserved.

Intertitle from the trailer

for "Sparrows."

35mm tinted nitrate positive (AFI/Tillmany Collection, 1979)

[36]

Rare outtakes from the Pickford Collection are also at the LC. One of the more interesting finds is footage from a national contest held in January 1929 that sent twenty-five young women and their chaperones to Los Angeles, California for a week as a promotion for Pickford's first sound film "Coquette." Local newspapers, in cities like Birmingham, Buffalo, Cleveland, and the District of Columbia, held the contest and provided female chaperones. The winners were selected through popular vote by friends and neighbors. They rode the Mary Pickford Coquette Special from Chicago to Los Angeles, were given a tour of the city, and went to Pickford's famous home Pickfair. The outtakes show the winners on a boat to Catalina Island, visiting the set of "Coquette," and spending time with the actress. The six reels include footage taken at Grauman's Chinese Theater in Hollywood on the film's opening night. Celebrities including Joan Crawford, Marion Davies, Cecil B. DeMille, and Norma Shearer were in attendance.

Pickford meets the winners

of the Coquette Promotional contest by their train the Mary Pickford Coquette

Special, in Los Angeles.

35mm nitrate positive (Pickford Collection, 1995)

[37]

The footage of the winners was used in promotional reels to be shown in local theaters. Two are known to exist, a "non-regional" version at UCLA and a"Buffalo edition" which features Buffalo winner Catherine Roos at the LC. The outtakes were preserved by the LC in 1988, but remain unavailable for research. The UCLA promotional reel is preserved and accessible, while the LC needs to copy its nitrate print of the " Buffalo edition." LC's material has more footage and is in better physical condition than the element found at UCLA . It also contains unique footage of director Fred Niblo.

Mary Pickford meets Catherine

Roos, winner of the "Coquette Promotional" contest from Buffalo, New

York.

35mm nitrate positive (Pickford Collection, 1995)

[38]

The LC also has outtakes of a process shot edited from the film "Sparrows." The shot labeled "Angel in a Barn," shows an angel waiting to take a dying baby from the arms of Mollie (Pickford). In the release version, Jesus comes for the child as Mollie sleeps. The unused processed shot was taken several times and the nitrate positive was tinted sepia. The 250 foot roll of film was donated to LC in 1995 and has not been preserved. LC and GEH have 16mm prints copied from the nitrate in the 1956 preservation of Pickford material at the USDA film lab.

An angel comes to take the

dying baby from Mollie's arms. Processed shot edited out of the

release version of "Sparrows."

35mm tinted nitrate positive (Pickford Collection, 1995)

[39]

There are screen tests of the unproduced "Faust" that Mary Pickford hired Ernst Lubitch to direct for her. The actress does not appear, but this important pre-production footage provides insight into Lubitch's creative outlook and possibly one of the answers to why Pickford shelved the project. It was preserved by the LC and a video cassette copy is able for viewing.

During a research trip to Dayton for nitrate film inspection, an LC employee

(Larry Smith) brought me a small rusty unlabeled can from the Pickford Collection

vault. George Willeman, the LC's Nitrate Film Vault Work Leader, and I identified

the small roll of camera negative as behind the scenes footage of Pickford

on the set of "Little Annie Rooney." The 70 feet of original nitrate

was preserved by the LC and a 35mm print is available for research purposes.

The same year, additional behind the scenes footage from "Little Annie

Rooney" was discovered in a dumpster outside the UCLA Film and Television

Archive.

Mary Pickford on the set

of "Little Annie Rooney."

35mm reference print (Pickford Collection, 2001)

[40]

In 1995, the Pickford estate donated location scouting footage called "Epic of the South" to LC. The footage on Eastman Kodak nitrate positive stock (1925 edge code) appears to be for the film "Coquette." It consists mostly of stock shots of New Orleans and its large southern homes. Curiously, the original reel is tinted and includes descriptive intertitles. The LC preserved this material in 1998 and it is available for research. The GEH also has a 16mm print (titled "New Orleans") from the Pickford Collection.

The LC is home to the only known surviving color footage of Mary Pickford with Douglas Fairbanks. The couple is playing golf at a resort in Mexico in a segment of a one-reel promotional film called "Holiday in Mexico" (1929). The film was preserved and made available in black and white only, but needs to have the color segments restored.

Rare color footage Pickford

and Fairbanks from the promotional short "Holiday in Mexico."

35mm Magna Color nitrate positive (AFI/Thunderbird

Collection, 1989) [41]

During WWI, Pickford starred in two short reel films, "Second Liberty Loan," and "100% American," to promote the purchase of war bonds. In "Second Liberty Loan," President Woodrow Wilson and several film stars, such as Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks and William S. Hart, highlighted the need for homefront participation in the war effort by purchasing bonds. LC has 35mm material which is unique to the archive and a viewing print is available. "100% American" is a one-reel story about a young woman (Pickford) who forgoes her usual pleasures (shopping) and activities (dancing) to save money for war bonds. This short film also stars Monte Blue, who appears with Pickford in her WWI feature film "Johanna Enlists." Both LC and GEH have 16mm viewing copies, and an incomplete version reissued during WWII in Canada called "100% Canadian."

Pickford and Fairbanks playing

to the camera in this home movie of her cousin's wedding shot at Pickfair.

35mm reference print (Pickford Collection, 1995) [42]

The majority of the Pickford-Fairbanks home movies can be found at MoMA in the Fairbanks Collection, but a 35mm nitrate negative of "Mary Pickford's Cousin's Wedding" (1925) is in the Pickford Collection at LC. The wedding takes place a Pickfair, the home of Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, with all of the Pickford's in attendance, including Jack, Lottie, and Charlotte. Fairbanks plays to the camera in his usual boistrous fashion, and wedding guests lounge on Pickfair's grounds. The original negative has been preserved and a researcher copy can be screened.

NOTES

[1] Frame enlargement courtesy of the Library of Congress

Motion Picture & Television Reading Room.

[2] These films are among the errors printed in books

America's Sweetheart (Scott Eyman), American Film Index, 1908-1915

(Einar Lauritzen and Gunnar Lundquist), Mary Pickford Comedienne

(Kemp Niver), American Film Personnel and Company Credits, 1908-1920

(Paul C. Spehr with Gunnar Lundquist)Pickford: The Woman Who Made

Hollywood (Eileen Whitfield), and Sweetheart: The Story of Mary Pickford

(Robert Windeler).

[3] For example these two titles appear in the books American

Film Index, 1908-1915 (Einar Lauritzen and Gunnar Lundquist) and American

Film Personnel and Company Credits, 1908-1920 (Paul C. Spehr with Gunnar

Lundquist).

[4] Frame enlargement courtesy of the Library of

Congress Motion Picture & Television Reading Room.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Letter, James H. Culver to Kemp Niver, February

2, 1960 (Pickford Collection, M/B/RS, LC); and Memorandum, John Kuiper to

Paul Spehr, David Parker, and Pat Sheehan, January 21, 1971 (Pickford Collection,

M/B/RS, LC).

[8] Letter, Kemp Niver to Dr. John Kuiper, July 10,

1974 (Niver file, M/B/RS, LC).

[9] Letter, James H. Culver to Willard Webb, April

18, 1956 (Pickford Collection, M/B/RS, LC).

[10] Memorandum, Williard Webb

to Director, Adminstrative Department, March 11, 1958 (Pickford Collection,

M/B/RS, LC).

[11] Frame enlargement courtesy of

the Library of Congress Motion Picture Conservation Center. Used by permission

of The Mary Pickford Foundation.

[12] First Convention of the HOLLYWOOD MUSEUM ASSOCIATES

for the Los Angeles County-Hollywood Motion Picture and Television Museum,

September 15-17, 1961 (Hollywood Museum Collection, Box 39, AMPAS).

[13] Letter, Matty Kemp to George Stevens, Jr., January

3, 1968 (AFI:Pickford Collection, M/B/RS, LC).

[14] Memorandum, Matty Kemp to Mary Pickford, January

2, 1964 (Pickford Collection, Box 39, AMPAS)

[15] Memorandum, Matty Kemp to Mary Pickford, October

7, 1964 (Pickford Collection, Box 49, AMPAS)

[16] Letter, David Shepard

to Matty Kemp, March 31, 1969 (AFI: Pickford Collection, M/B/RS, LC).

[17] Report, Robert Cushman for the American Film

Institute and the Library of Congress, Motion Picture Section, July 18,

1970 (Pickford Collection, M/B/RS, LC.

[18] Frame enlargement courtesy of the Library of Congress

Motion Picture & Television Reading Room. Used by permission of The

Mary Pickford Foundation.

[19] Frame enlargement courtesy of

the Library of Congress Motion Picture Conservation Center. Used

by permission of The Mary Pickford Foundation.

[20] Frame enlargement courtesy of the Library of Congress

Motion Picture & Television Reading Room.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Frame enlargement courtesy of

the Library of Congress Motion Picture Conservation Center.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Frame enlargement courtesy of the Library of Congress

Motion Picture & Television Reading Room.

[26] Frame enlargement courtesy of

the Library of Congress Motion Picture Conservation Center.

[27] Frame enlargement courtesy of the Library of Congress

Motion Picture & Television Reading Room.

[28] Ibid. Used by permission of The

Mary Pickford Foundation.

[29] Frame enlargement courtesy of

the Library of Congress Motion Picture Conservation Center. Used

by permission of The Mary Pickford Foundation.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Frame enlargement courtesy of the Library of Congress

Motion Picture & Television Reading Room.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Frame enlargement courtesy of

the Library of Congress Motion Picture Conservation Center. Used

by permission of The Mary Pickford Foundation.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Frame enlargement courtesy of the Library of Congress

Motion Picture & Television Reading Room.

[36] Frame enlargement courtesy of

the Library of Congress Motion Picture Conservation Center.

[37] Ibid. Used by permission of The

Mary Pickford Foundation.

[38] Ibid. Used by permission of The

Mary Pickford Foundation.

[39] Ibid. Used by permission of The Mary Pickford Foundation.

[40] Frame enlargement courtesy of the Library of

Congress Motion Picture & Television Reading Room. Used

by permission of The Mary Pickford Foundation.

[41] Frame enlargement courtesy of

the Library of Congress Motion Picture Conservation Center.

[42] Frame enlargement courtesy of the Library of Congress

Motion Picture & Television Reading Room. Used

by permission of The Mary Pickford Foundation.