PROJECT DESCRIPTION

Mary Pickford was one of early cinema's pioneers. During her 24-year screen career, she was creatively involved in an estimated 204 productions as an actress, writer, or producer. In addition, she co- founded United Artists, the first independent distribution company. Because Pickford was a cultural icon and an international celebrity created by the cinema, she is usually described as the first great movie star. Unfortunately, over the decades her on-screen persona has been misrepresented by film critics and scholars alike. And persons who experienced the Pickford phenomenon when it first unfolded are now difficult to find. To reevaluate her work and understand her fame, it is necessary to look at her films with a fresh eye.

Fortunately, most of Pickford's movies survive in motion picture archives around the world. In 1997, I began a project to create a map of their locations, as well as to inspect and compare the content and quality of the material. My goal is to aid archives in preserving and restoring unique or deteriorating materials before they are lost. The information acquired during this project will not only secure preservation of Pickford's films, but improve access and provide vital information for scholars, researchers, and film enthusiasts.

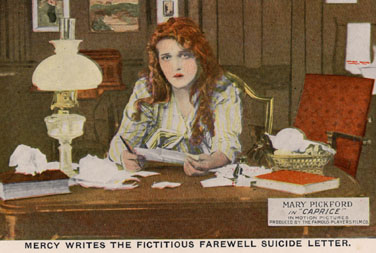

Postcard from "Caprice"

(1913), one of ten lost Pickford features.

My search for Pickford films began at George Eastman House (GEH) in Rochester, NY, but my interest in the actress began during my undergraduate studies at Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio. While enrolled in a silent film course, I became intrigued by Pickford both on and off screen, especially the level of power and stature she attained. She began producing her own pictures in 1916, making one of the highest salaries in Hollywood, and became the most recognizable woman in the world. Due to her Victorian image, the label "America's Sweetheart," and criticism by a number of feminist film scholars, I assumed that the actress's screen persona embodied the era before women's liberation. I accepted that Pickford, when not portraying sickly-sweet child roles, applied similarly exaggerated and regressive concepts of female fragility and purity to her older roles. I quickly realized how ridiculous and uninformed my opinions were after watching "Sparrows," one of actress's late silent films.

"Sparrows" is a Dickensian tale of an orphaned young woman (Mollie) who lives on a baby farm. She stands up against the owner, the villainous Mr. Grimes, for the survival its young residents. Grimes makes few provisions for the children, so Mollie (Pickford) struggles to feed, clothe, and protect them. When one of the children (a toddler kidnapped from a rich family and hidden at the baby farm) becomes a liability, Grimes plans to dispose of her in a nearby swamp. Mollie stands guard over the child with a pitchfork, and later executes a daring rescue. She leads the children off the baby farm (with the kidnappers and Grimes in pursuit) and through the swamp with its massive trees, creeping dead branches, and treacherous alligators. Danger is everywhere, but the brave Mollie gets all of the children out. Even with the film's happy and patriarchal Hollywood ending (the toddler's wealthy father brings Mollie into his home to "mother" his child and the others), I realized that there was more to Mary Pickford than history remembered.

Mollie confronts Mr. Grimes

with a pitchfork in "Sparrows" (1926) [1]

A couple of years later, while studying film preservation and restoration at the GEH, I screened additional Pickford titles in the archives collection. The gulf continued to widen between my perception of the Pickford persona and the opinion of critics like Molly Haskell and Marjorie Rosen, authors of From Reverence to Rape and Popcorn Venus respectively (both books are required reading in many film courses). The writers depict "America's Sweetheart as "angelic"[2] and "saccharine [3]."Haskell admits that the Pickford image is complicated and misunderstood, and that "there has simply not been an adequate revival of her films to allow for reappraisal."[4] Still, she argues that Pickford's roles were "calculating" and "cheerful as a month of Sundays."[5]

Rosen is disturbed by Pickford's screen persona, which she describes as "stultifying the growth of women's self-image" with her "thick golden curls, cherubic body and pretty face."[6] She inaccurately portrays the Pickford character as one that "would not disturb the status quo, flirt with immorality, or exude sexuality."[7] Anyone who has seen even a few of Pickford's films knows she is a champion of the underdog, who lives in a world where morality is not easily defined. Good people have babies out of wedlock, steal out of need or desire, and can be alcoholic parents who inadequately care for their children. The typical Pickford character lives in such poverty and hardship that "sweetness and light" are rarely seen. She survives this world with her mind, body, and soul intact, while helping others do the same.

Her on-screen sexuality (viewed as nonexistent or childlike) has been misread, and her prowess in physical and verbal confrontation completely ignored. Mary Pickford would never be mistaken for a vamp, but it is incorrect to label her "asexual." Her sexuality, age appropriate to each role, is acknowledged in nearly every film. Playing a prepubescent girl in "A Little Princess" or "The Poor Little Rich Girl" leaves little room for such storytelling, but Pickford portrayed the girlfriend, wife, and mother in dozens of features and numerous short films. More interesting, and less often discussed, is her ability to escape a sexually defined role. Her characters have the complexities of any typical male protagonist--free to be the lover, husband, or father without sacrificing his individuality. Pickford's willingness to fight (verbally as well as physically) is apparant in numerous films. Bullies, snooty rich kids, errant boyfriends, and sexual predators all find themselves on the receiving end of her temper. She uses her body, rocks, whips, and guns as weapons to defend herself and others from physical or emotional aggression. There is rarely a time when she bites her tongue or cowers in fear. In "Way Down East" (1920), Lillian Gish plays a character who needs to be rescued from an ice floe, but Pickford portrays the kind of young woman who would have saved her. Strength, rebellion, and heroism are at the heart of her screen persona. The fact that it comes in a small, angelic, feminine package does not nullify its power, but reinforces the idea that women are not necessarily fragile.

Protecting her lover from

Union soldiers in "The Informer" (1912)

[8]

In the 1950s and 1960s, film historians Edward Wagenknecht and James Card were among the first writers to challenge the myth that surrounded Pickford's legacy. In recent years, Kevin Brownlow, Robert Cushman, and Eileen Whitfield have tried to rehabilitate the actress's screen image. Though progress has been made, battling misconceptions with words and still images is not enough. Preserving and making her work accessible will contribute significantly to restoring Pickford's reputation. Her movies, most of them silents, speak to her legend and popularity more than words ever can.

From the very beginning, it was clear that the Pickford Project would be complicated and labor intensive. Simple research on the actress still had to be done. In how many films was Pickford creatively involved? Where were they located? Biographies and film histories helped create a filmography for the actress, writer, and producer. Archival holdings were available through the American Film Institute and the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF) databases. Ron Magliozzi's book Treasures From the Motion Picture Archives was another great resource for information.

Initially, I decided to limit the project to FIAF archives in the United States with the possibility of further research in Europe. I also chose to focus on Pickford's work from 1909-1933, excluding movies she produced after her acting career ended. To inspect, compare, and catalog the film materials it was necessary to obtain archival access and funding. This was no easy undertaking, but with my education at GEH and a number of connections made through its preservation school, I was able to create interest in the project. The Mary Pickford Foundation, a financial trust set up to provide funds for Pickford's favorite charities, offered a small grant to research the actress's film holdings at GEH.

The GEH portion of the research began in the summer of 1997 and was completed in three months. A number of unique titles, including "The Mirror" (1911), "Behind the Scenes" (1914), and "A Romance of the Redwoods" (1917), can be found at this archive. And GEH has a rare two strip Technicolor screen test of the actress. Only after leaving GEH did I learn that Pickford had a strong personal and professional interest in the museum. She attended the opening in 1949, and donated the funds for the museum's acquisition of her films. Pickford also kept a friendly correspondence with Film Department staff James Card and George Pratt, and the institution honored her with two "George Awards" for her contribution to cinema. At present the Pickford papers at GEH are not accessible.

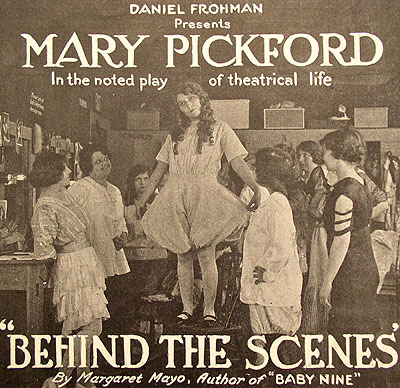

Advertisement for "Behind

the Scenes" from Motion

Picture News

In October of 1997, I headed to Los Angeles to investigate the Pickford material at the UCLA Film and Television Archive (UCLA) where my task was completed in three months. The archive has a rare title called "A Manly Man" (1911) and a few features that are the best of the surviving material, these include "Tess of the Storm Country" (1914) , "The Little American" (1917), "Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm" (1917), and "The Love Light" (1921). UCLA has an excellent track record for restoring Pickford films and is interested in acquiring more of her work. Recently, the archive has begun to collaborate with the Pickford Foundation on projects involving films in the foundation's private collection. New information on Pickford materials will be updated when it is available.

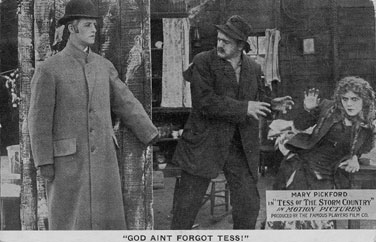

Promotional postcard from

"Tess of the Storm Country" (1914)

The project's greatest challenge was the Library of Congress (LC). The archive has the world's largest collection of Mary Pickford titles. They house her personal film collection (donated in 1946), the majority of her Biograph titles in the Paper Print Collection, and additional titles donated from various collections. As is typical of many moving image archives, the LC cannot easily generate a list of holdings for one particular film artist, regardless of her or his status. Rough estimates can be made, but for a definitive inventory every card catalog, file, and database must be searched. In the summer of 1998, I spent eight weeks gathering information, which was necessary to determine the time frame for my research and to apply for funding.

I discovered that the LC has all but three of Pickford's 108 Biograph titles, eight of her eleven surviving IMP one-reelers, and thirty-one of her feature films. The LC also has a small collection of home movies, trailers, promotional footage, and newsreels that include the actress. I anticipated nearly a year to properly evaluate these Pickford materials, four times longer than the time needed at GEH and UCLA. Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities came two years later and I was able to begin working at the LC in June of 2000.

The LC has a number of rare Pickford film titles, including "The Dream" (1911), "Sweet Memories" (1911), and "Cinderella" (1914). They also have the best of the surviving material of "Madame Butterfly" (1915), "Sparrows" (1926), and "Kiki" (1931). The LC's unique Pickford items, include the trailers for "Sparrows" and "Coquette" (1929), as well as "Behind the Scenes Footage of Mary Pickford on the Set of Little Annie Rooney" (1925). Since my research at the LC began, the archive has taken a serious interest in my findings and recommendations. A number of preservation projects are in the works, as well as a collaborative restoration of "Pride of the Clan" (1917) with the Pickford Foundation.

Mary Pickford on the set

of "Pride of the Clan" (1917)

My search for Mary Pickford film legacy continues. A study of films at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City is a necessary step. And after locating rare early features in England, France, the Netherlands and Czech Republic, I have incorporated the European FIAF archives with significant Pickford materials into my investigation. While waiting for funding to complete the research phase of the project, I am busy organizing data and writing about the work accomplished to date. The publication of the project commences with this website and an article on the state of the Pickford Collection at the LC, which appeared in The Moving Image (Spring 2003).[9] It is my goal that this website will serve researchers, archives, and film enthusiasts interested in Mary Pickford until the project is published in its final form. For detailed project reports and Pickford holdings for participating institutions, an up-to-date filmography, and acknowledgments, please use the links below.

[1] Frame enlargement courtesy of the Library

of Congress Motion Picture & Television Reading Room. Used by permission

of The Mary Pickford Foundation.

[2] Majorie Rosen, Popcorn Venus [New

York: Avon Books, 1974], 34.

[3] Molly Haskell, From Reverence to Rape [Chicago: The University

of Chicago Press, 1974], 58.

[4] Ibid, 59.

[5] Ibid, 61, 58.

[6] Majorie Rosen, Popcorn Venus [New York: Avon Books, 1974], 34.

[7] Ibid, 35.

[8] Frame enlargement courtesy of the Library of Congress Motion Picture &

Television Reading Room. Used by permission of The Mary

Pickford Foundation.

[9] Christel Schmidt, "Preserving Pickford: The

Mary Pickford Collection and the Library of Congress," The Moving

Image, vol. 3, no. 1 [2003]: 59-81.

UCLA Film and Television Archive Report

Pickford Archival Film Holdings